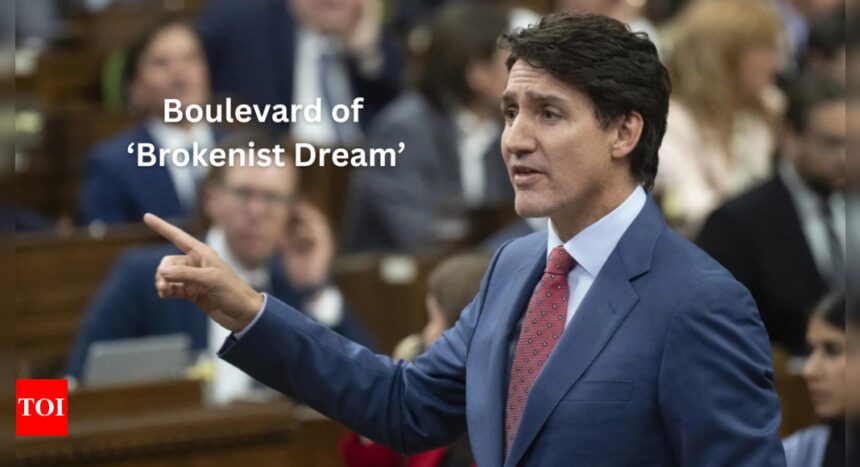

Justin Trudeau, the Canadian Prime Minister, made headlines recently when he coined the term “brokenist” during a parliamentary session. This unusual word choice was his attempt to criticise the opposition’s approach to policy and the nation’s economy. However, the term sparked widespread mockery both inside and outside Parliament, with many questioning its validity and meaning.The incident draws attention to the broader subject of parliamentary language and what constitutes appropriate or inappropriate, often termed “unparliamentary”, speech in legislative assemblies.

What is Parliamentary and Unparliamentary Language?

Parliamentary language refers to the decorum expected from members during debates and discussions within legislative assemblies. It encompasses the tone, phrasing, and the general respect owed to fellow members and the institution itself. While members are expected to engage in heated debates, the language used must maintain a certain level of dignity and respect, refraining from personal attacks or derogatory remarks.

Unparliamentary language, on the other hand, refers to terms, phrases, or expressions that are considered inappropriate in parliamentary discourse. These typically include accusations of dishonesty, insults, or any form of derogatory language directed at other members. The definition of what constitutes unparliamentary language can vary significantly from country to country, but the underlying principle remains the same: it is language that disrupts the dignity and decorum of parliamentary proceedings.

In the Canadian House of Commons, the Speaker has the authority to determine whether certain language crosses the line. While there is no comprehensive list of prohibited words, precedent and the discretion of the Speaker guide decisions on whether a term should be withdrawn or apologised for. In Trudeau’s case, while “brokenist” was not ruled unparliamentary, the term was criticised for being vague and failing to contribute meaningfully to the debate.

Justin Trudeau’s “Brokenist”: An Example of Modern Political Language

The term “brokenist” emerged during a heated session in which Justin Trudeau aimed to highlight the alleged negativity and obstructionism of the opposition, particularly the Conservative Party, under its leader Pierre Poilievre. Trudeau’s use of the term seemed to suggest that the opposition was overly focused on portraying Canada as “broken,” a theme Poilievre had used repeatedly in his critique of Trudeau’s government.

While Trudeau likely intended “brokenist” to be a shorthand for this negativity, the unusual nature of the word prompted widespread derision. Media outlets and social media users were quick to pounce on the awkward phrasing, and the opposition capitalised on the moment, using it to portray Trudeau as out of touch. Despite this mockery, the incident also opened a broader conversation about the evolving nature of political language and the fine line between clever rhetoric and confusing jargon.

Parliamentary Insults: A History of Creative (and Unparliamentary) Language

While “brokenist” may have been intended as a subtle political jab, parliaments around the world have seen far more overt and offensive language used over the years. In many legislative assemblies, MPs have employed insults and accusations that push the boundaries of parliamentary etiquette.

In the UK, for example, some notable unparliamentary terms include “liar,” “blackguard,” and “hypocrite,” all of which have been ruled out of order in the House of Commons. One famous example of a creative parliamentary insult came from Winston Churchill, who, rather than outright calling someone a liar, famously used the phrase “terminological inexactitude” to avoid breaching parliamentary rules while still making his point.

Canada, too, has had its share of colourful language in Parliament. In 1971, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (Justin Trudeau’s father) famously mouthed the words “fuddle duddle” when accused of using profanity during a heated exchange. The phrase has since become a part of Canadian political folklore, illustrating how even veiled insults can capture the public’s imagination.

Other terms that have been ruled unparliamentary in Canada include “liar,” “racist,” “scuzzball,” and “traitor.” Despite the strict regulations, MPs have often found creative ways to push the limits of what is acceptable, using indirect insults or wordplay to convey their disdain for opponents.

The Evolution of Language in Democracies

The use of language in democratic institutions has always been a key part of political strategy. From ancient Athens to modern-day parliaments, rhetoric has played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and influencing policy. However, as societies and cultures evolve, so too does the language used by their representatives.

In the early days of parliamentary democracy, debates were often characterised by formal, sometimes archaic, language. Insults were veiled, and speakers relied heavily on metaphor and euphemism to avoid directly offending their opponents. However, as politics became more accessible and the media began to play a larger role in disseminating parliamentary proceedings, the language used in legislatures became more direct and, at times, more abrasive.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, political language has continued to evolve, influenced by the rise of mass media, social media, and a general shift towards more informal forms of communication. While insults and accusations have always been a part of parliamentary life, the way they are delivered has changed. Politicians are now more likely to use soundbites and catchphrases, knowing that their words will be replayed on television, radio, and social media platforms.

However, with this increased visibility comes a greater risk of backlash. As Justin Trudeau discovered with his use of “brokenist,” the line between clever political rhetoric and confusing jargon can be thin. In today’s media-saturated world, even the smallest verbal misstep can quickly become a viral moment, overshadowing the substance of the debate.